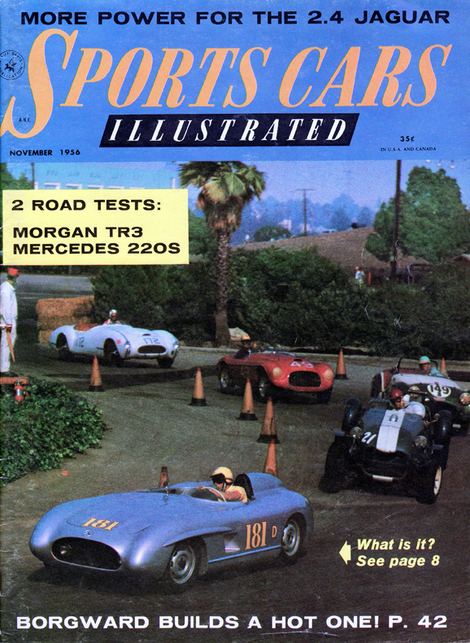

1956 Mercedes 300 SLS (Porter Special)

Continuing with my interest in historic sports car racing and sports racing cars I found this article about Chuck Porter's "American SLS" a 1956 Mercedes SL that was destroyed during delivery (or so the story goes) and resurrected as a very competitive race car. One that has subsequently made appearances in famous movies includung "On the Beach" and more recently at a Goodwood Revival event.

This car is a good example of the force and creativity exhibited in America in the 40's; 50's; and 60's. Hot-rodding and sports car racing were in their infancy and builders had to fabricate almost everything as the number and variety of after-market parts were not available. It just was not a major industry yet. Builders had to rely their experience and creativity to fabricate and out of this came some of the most exciting cars in our history.

This article is recreated from Sports Cat Illustrated November 1956.

The Screamers' KISSIN' COUSIN

by Jim Mourning & Russ Kelly - photos: by Bob Rolofson

When the cars pulled onto the starting grid for the main event at the Pomona circuit recently, eyes popped all through the pits. There, apparently , lined up with an assortment of Ferraris, D. Jaguars, and back yard bombs, was a Mercedes SLR.

Actually, of course, it was nothing of the sort, for the factory retired those astonishing racers from active competition many months ago. What drivers and mechanics were gaping at was the Mercedes SLS (the second S for "Scrap"), a Special making its debut out of Chuck Porter's body shop in Hollywood.

The marked resemblance to the 300 SLR is more than mere coincidence. Porter designed the car from his own shop walls, which are adorned with European race posters picturing the silver screamers. The only deliberate deviation are a higher front end - to provide clearance above the stock radiator - and the switching of the headlights from the fenders to the grill opening.

The story of the Mercedes 300 SLS is every bit as striking as its appearance. It all began when a 300 SL went out of control, flipped on its lid, skidded 1300 feet and burned. The driver came out of it feeling not much worse than the insurance company when they had to 'total' the car.

It cracked, broke or burned nearly everything listed in the stock inventory. And the remains were all bundled up in a package that measured about 3 feet at the top of the 'gullwing' doors, which point was about 3 inches lower than the hood line at the time.

For six months the car sat in a wrecking yard collecting rust and corrosion. At that point, Porter, a bodyshop owner, entered the picture. This looked exactly like what he had been searching for - a basis for a really potent special at a price he could afford. A few days and $500 later, he dragged the car away. And "dragged" is the right word; one side of the frame touched the ground and piecers trailed out behind it.

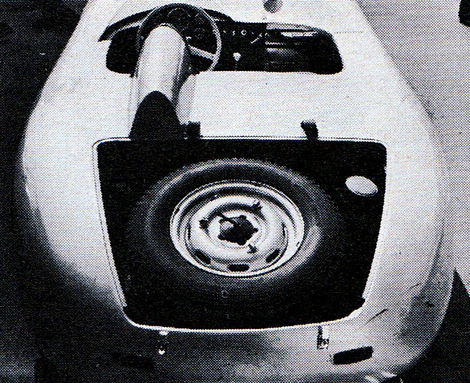

Dunlop Extra Super Sport spare is carried in aft compartment in compliance with FIA code.

Dunlop Extra Super Sport spare is carried in aft compartment in compliance with FIA code.

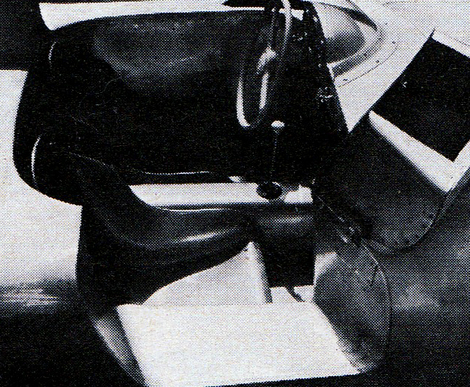

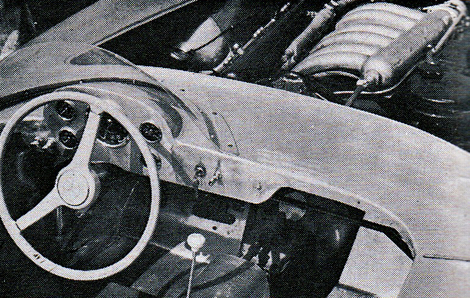

Dash panel, seats, and placement are Porter's design. Wheel and shift are stock Mercedes,

Dash panel, seats, and placement are Porter's design. Wheel and shift are stock Mercedes,

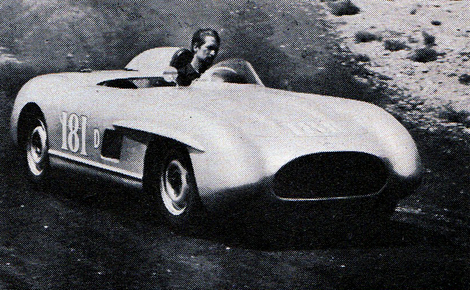

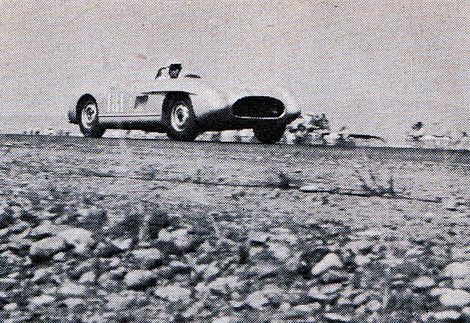

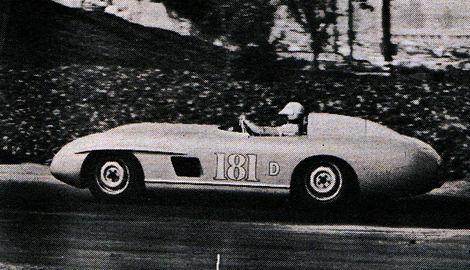

Kelly drifts Stuttgart imitation through the esses at Willow Springs.

Kelly drifts Stuttgart imitation through the esses at Willow Springs.

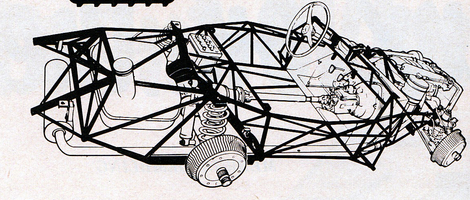

Porter considered the situation from all angles and came to the conclusion reached by many car lovers before him - there isn't much you can do to a Mercedes to improve it mechanically. Consequently, he decided to restore the chassis and engine as new and concentrate on cutting the weight down by building a new super light open body resembling as closely as possible the factory SLR.

When work began, he probably entertained doubts as to whether the $500 buy had been such a bargain after all. Many hours of work with a torch were required to remove the body. When the body was removed, it revealed a mass of broken and bent tubes that little resembled the neat geometric pattern that was covered at Sutttgart. In addition, fire damage had been more extensive than Porter had first realized. Few of the smaller aluminum castings could be salvaged. Unfortunately, this included expensive brake drums and the fuel injection pump.

Rolling up his sleeves and recuriting his friends, Porter began what is probably one of the fastest jobs of Special building on record. Only by extensive use of the frame rack was it possible to pull the chassis frame back into enough shape so that bent tubes that were beyond repair could be replaced. By working eight and ten hours a night after his shop closed, the damaged parts were either repaired replaced by the end of the week and the rebuilding began. whenthe chassis was ready for wheels, Porter made his first departure from stock by fitting magnesium wheels.

In addition to the fuel injection pump, a major casualty, the engine suffered from having been left in the open for six months with a damaged cam cover. However, by careful cleaning most of the original parts could be used in reassembly. The only improvement on this engine, almost new at the time of the accident, was the installation of the factory's optional competition cam.

With the car ready for the body, Porter purchased $500 worth of .064 aluminum, took his plans to Jack Sutton, noted California body builder who formed the compound bends, then carted the bundle back to his shop to tackle the job of final shaping and fitting the skin to the renovated discard.

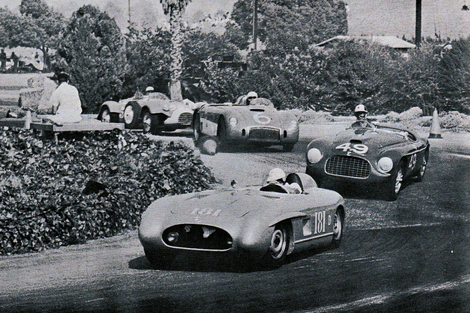

At San Diego, Chuck Porter placed second in class to one of Enzo's potent 3 litre Monzas.

At San Diego, Chuck Porter placed second in class to one of Enzo's potent 3 litre Monzas.

*The 300 SLS coming through one of the tightest turns at Pomona. In spite of difficulty with fuel injection timing which left the car embarrassingly short on revs, Porter finished eighth overall, and recorded 3rd in class.

*

*The 300 SLS coming through one of the tightest turns at Pomona. In spite of difficulty with fuel injection timing which left the car embarrassingly short on revs, Porter finished eighth overall, and recorded 3rd in class.

*

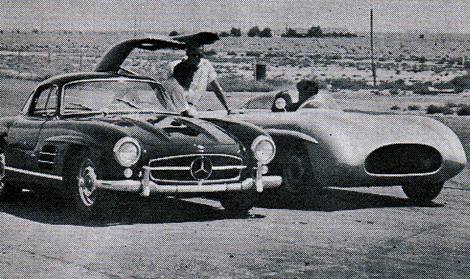

Reventlow, Porter, and Kelly (in car). The fast aluminum bodied 300 SL was bought in as comparison to the SLS.

Reventlow, Porter, and Kelly (in car). The fast aluminum bodied 300 SL was bought in as comparison to the SLS.

This kind of a car taking shape in a body shop located in Hollywood couldn't escape a lot of attention. Mysterious rumors started; the most popular reported that Porter had a pipeline to the Mercedes factory which was supplying him with full information so he could bring the engine up to 300 SLR specifications. This tale was apparently widely believed by people who find it difficult to count above six. At any rate, the bench racers kicked the car around quite a bit and their arguments about whether it would go or not usually deadlocked at the it-will, it won't stage.

Most of the conflicting reports on the performance possibilities of this car can be settled by simple arithmetic. A good slightly modified 300 SL fuel injection engine will pull 240 BHP on an engine dyno. Chuck Porter's SLS weighs 1750 pounds. And another 250 for fuel, oil, and driver and you come up around eight pounds per horsepower. A modest acquaintance with the rear suspension of the gullwing Mercedes assures you that the swing axle will efficiently translate into acceleration a high percentage of the torque coming off the back of the gearbox. So here in the tricky world of automobile arithmetic is a car that should perform creditably........but how about the two most important variables - the ability of the driver and the handling characteristics of the car on the course?

Porter has the often-heard answer for the first question, "If I can't drive it, I'll find someone who can." This is of course, a loaded statement, but Porter is believable when he says it. For the second of the big questions, Porter invited SCI to determine the answer at Willow Springs.

It seemed a good idea that since the SLS is little more than stock, with the exception of the light weight body, that it should be directly compared on the course with a fast 300 SL coupe. It turned out that the fastest coupe on the west coast even though in concours condition, was available. Belonging to Lance Reventlow, it is fitted with special factory aluminum body, has a number of magnesium castings substituted for stock aluminum ones and has magnesium wheels. The suspension has recieved attention in the form of competition springs and shock absorbers. The engine has the racing cam shaft and has also had a few hours spent on it by people who know what they're about.

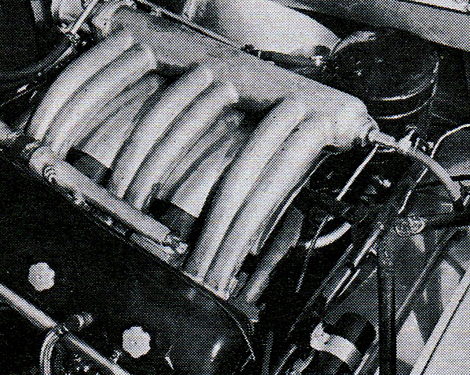

Mercedes 300 SL engine after restoration. There is virtually no trace this engine was once a melted mess of metal.

Mercedes 300 SL engine after restoration. There is virtually no trace this engine was once a melted mess of metal.

Steering wheel is stock 300 SL, as are instruments, and stick shift. Note floor step for leg comfort.

Steering wheel is stock 300 SL, as are instruments, and stick shift. Note floor step for leg comfort.

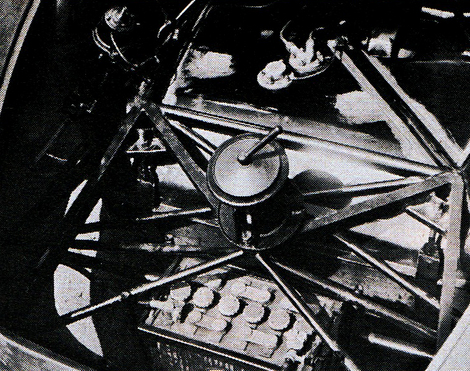

Removed spare uncovers tank, high boost fuel pump (left), battery, and part of rear suspension.

Removed spare uncovers tank, high boost fuel pump (left), battery, and part of rear suspension.

Porter at Pomona. This was the first race after restoration. At Santa Maria, the 300 SLS ran to an overall first place in one race.

Porter at Pomona. This was the first race after restoration. At Santa Maria, the 300 SLS ran to an overall first place in one race.

On the trip to the course, the 300 SL proved to be the sort of of a road machine you dream about but never even have a chance to use - the finest things in life are very costly indeed.

Fully warm from its run from Los Angeles, the coupe was used to scout the course. A few fast laps brought home forcibly the fact that even if it is "without exception a Gran Turismo machine par excellence", it still is'nt a car you can enjoy in closed course competition. When you're in a hurry the acceleration can be called almost frightening but that's nothing compared to what you might call trying to stop. Since the end of every straight is usually attached to a corner, the ability of the breaks to deliver you there at sometimes risky velocities sets you up beautifully for the Teutonic Sunday punch - this car in a corner will pick you up on your slightest indiscretions and turn you every way but loose.

The habit of coming suddenly and violently unglued is supposed to be a little more subdued with competition suspension, some drivers even claiming that with it you can actually pick the point you're going to leave the road. These are harsh words, but for all its publicity, the 300 SL, is not a racing car and nothing could make it more apparent than a switch from it to Chuck Porter's SLS.

When you drop into the sparsely padded seat of the SLS, you're immediately aware that Porter has magically caught that indefinable feel of a business-like car as well as the looks. All the controls are placed conventionally and comfortably. Most of the instruments are stock, although a speedometer is not fitted. After the ritual of checking the pedals for foot clearance, (you've only got to catch your foot once between brake and throttle pedal to find out how really hard some little things are to explain), a flip of the fuel pump switch, a quick turn and release of the ignition key and about 240 bhp sit idling quietly and waiting.

The clutch is surprisingly light in operation but has a healthy bite. The standard first gear is of a fairly low ration and makes light work of getting this car off the mark.

Trials:

The first laps were as sedate as an old-fashioned waltz. The coupe had made an indelibile impression, but it didn't take long for the obvious ability of the SLS to get through. To put it bluntly, the car handles.

Although some of the characteristics of the coupe are still apparent, they are so to a lessor degree. On entering a fast bend, caution is demanded just as with the coupe because condition of oversteer is still present. The latitude for an error in judgement just isn't as great as it might be with a car of neutral, or understeering, characteristics. The brakes are excellent and according to Porter, they have never given trouble through fading. Although acceleration below 60 mph is not shattering above 60 it's pretty stout.

One hundred and twenty-five mph could be reached consistently by the end of the main straight when lapping seriously. The lack of everything it takes to really get out of the chute does not hurt the speed at the end of a quarter mile, 103 once being recorded, but it does reflect itself in elapsed time. Best elapsed times are in the neighborhood of fourteen seconds for the standing quarter. There is the definite feel of plenty of hp at the rear wheels in cornering that is reassuring and this combined with slight oversteer makes interesting work of Willow's tight corners.

During the afternoon Reventlow and Porter traded cars in a generous manner, with Kelly making sure that he wasn't forgotten (did I hear someone say something about a nice job?)

In this little game of musical chairs, played here with $10,000 automobiles, each of the drivers found himself to be on average of ten to twelve seconds per lap faster with the SLS than with the coupe. In view of the high speeds involved, this is an outstanding testimonial for the handling of Porter's car.

After intially trying the car, I remarked to Porter that it handled surprisingly well. It took me awhile to recover from the salty statement that came back from behind Porter's ever present cigar. In essence it was, "What did you expect?"

Porter's right, it isn't surprising that this special is a potent racing car. It's just surprising that someone didn't think of it sooner.

The 300 SL prototype of 1952 that had all the competition running around in circles was a hot rod built by Uhlenhaut in the Mercedes factory out of stock production components. The stock SL of today is by all indications only heavier and possibly higher powered version of that startling 1952 competition car.

Porter had the right idea, apparently so simple that it didn't occur to anyone else. Just building a super light weight body on the SL, he made himself a reasonable replica of a car that would still not be outclassed today, the Mexico 300 SL.

The record of the car in races to date has been an encouraging one for Porter, whose road racing career began with the completion of the SLS. Although he had a successful career as a midget driver, he wasn't too certain of his ability to adjust to a road circuit.

SLS's RECORD:

The first actual test of the car came at a local drag strip. Speeds of 100 to 105 mph were recorded at the end of the standing quarter. Not too impressive when it's remembered that overall competition this car runs against the Murphy Buick and the D. Jag, but creditable enough for what Porter calls an engine straight from the junk yard.

In it's first race at Pomona, California, the car proved reliable and stable, recording third in class and eighth overall even through difficulty with the fuel injection timing left the car woefully short on revs. At Santa Maria, run under SCCA rules, Porter was accepted in the novice race and ran off and hid from everybody for an overall first place. This quickly graduated him from the classification of novice to senior driver where his entry where his entry in the senior main event gained him another first in class. A few weeks later at San Diego, in Saturday's racing, he placed second in class to one of Enzo's very potent three liter Monzas. In the Sunday main event, the reliability of the Mercedes saw him outlast the Ferrari and he gained another class first when the Monza lost its gearbox.

With five starts, three of them class wins, one second and one thied and an overall first in the novice class, with no retirements and with a driver who admits himself to be inexperienced, Porter has really set a precedent in Special's Building. There's only one hitch. What else can be done to improve its performance?

The engine is notoriously hard to improve upon. Extensive bench testing and road testing of each SL before it leaves the factory insures that near maximum is being obtained. The camshaft can be changed to advantage and slight alterations in the injection timing can be made with noticeable improvement. Other than this, tuning becomes a series of little dodges, like running twelve quarts of oil instead of fourteen and blanking off the radiator so that the oil temperature is maintained at a high operating level or like changing the distributor rotor from the type that does not have the resistor.

Little could be done with the compression ratio without really extensive modifications. Stock clearances between exhaust valve and piston on the exhaust stroke is one millimeter, or 39 teenie weenie thousandths of an inch. This should give SL owners with a heavy foot the fits.

In contradiction to this, the performance of some of the SL's that ran the Millie Miglia would lead you to believe that somebody had monkeyed with them, and not just changed distributor rotors either. If the factory does have further modifications for the SL engine, they will undoubtedly let Porter know about them.

CHASSIS:

The chassis suspension, and body need very little modification from a performance standpoint. The installation of competition shock absorbers and springs combined with the low weight and lowered center of gravity leave little to be desired, although the new little to be desired, although the new low pivot point rear axle might result in higher speeds through the corners and better acceleration out of them. The brakes seem more than adequate. The available axle ratios make it possible to suit almost any course conditions.

Porter has proved pretty well that he has initiative, and you can be sure that the performance of this car will not remain static.

Perhaps this would be a good time to say a word about Porter and other specials' builders. Their cars are fast, terrifically so, compared to what you normally drive. All you have to do is unravel one of these things down off the hill and into the sweeping corner at Willow to feel a stir of admiration for these guys that build and race them.

Reventlow, who has proved himself a pretty heady and competent driver, made a statement that I heartly agree with after trying the SLS, "It goes!"

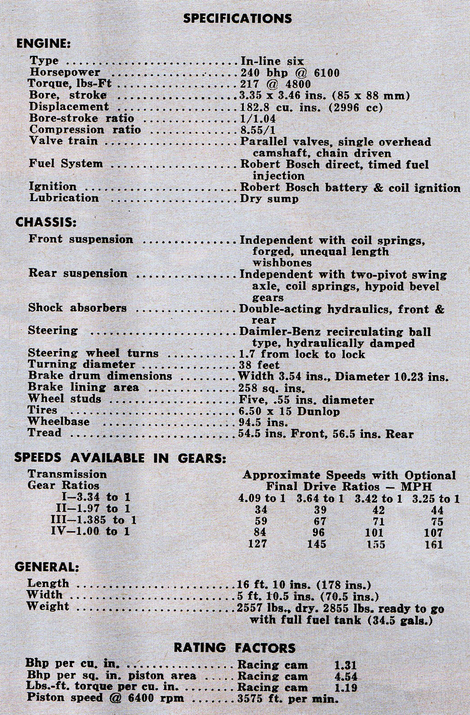

Specification Sheet.

Specification Sheet.

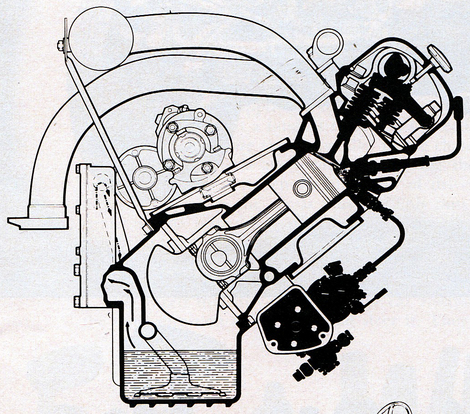

Drawing of 300 SL engine. Damaged parts included injection pump, cam cover, and intake tubes.

Drawing of 300 SL engine. Damaged parts included injection pump, cam cover, and intake tubes.

It took a week to straighten and bend and replace the bent and cracked tubes to the original form, shown in the drawing.

It took a week to straighten and bend and replace the bent and cracked tubes to the original form, shown in the drawing.

Information on the original Mercedes 300 SLR:

Despite a misleading name, the Mercedes-Benz 300SLR was based neither on the famous 1954 300SL road car, nor the earlier 1952 race car, although it bears a strong resemblance to both (including, in the coupe version, the distinctive 'gullwing doors'). Instead, it was based on the 1954-1955 Formula 1 Mercedes-Benz W196 race car; it was Mercedes' marketing department, who found 'W196S' an uninspiring name, who ordered the name '300SLR'. It is generally accepted that this name references the car's lightweight construction as 'Sport Leicht Rennen'.[citation needed] The car was of a front-mid-engined design (where the engine block is squarely behind the front axles), to give more neutral front/rear weight distribution. It used a spaceframe chassis and magnesium-alloy (Elektron) bodywork, which has a specific gravity of just 1.8 (for reference, the S.G. of iron is 7.8), both of which contributed to a dry weight of just 880kg. The preceding Formula 1 car's 8 cylinders in-line engine was used, increased in capacity from 2,496.87 cc (76.0 x 68.8 mm) to 2,981.70 cc (78.0 x 78.0 mm). This boosted output from 290 bhp at 8,500 rpm to about 310 horsepower at 7,400 rpm, depending on the intake manifold; maximum torque of 234 lb.-ft. came at 5,950 rpm (193.9 psi bmep), providing strong pulling power. The engine was longitudinally mounted, and was canted over at a 33-degree angle to lower its profile for aerodynamic reasons, resulting in the distinctive bonnet bulge on the passenger side of the car. The engine was also unusual in that it used desmodromic valve actuation instead of springs. Fuel injection was still a novelty then. The engine protruded some way back into cockpit, forcing the monoposto version drivers to straddle the driveshaft and clutch bellhousing with his feet to reach the pedals. To reduce crank flexing, power takeoff from the engine was at the center of the engine, via a gear, rather than at the end of the crankshaft. This was not the only oddity of the drivetrain - the car was fitted with vast inboard drum brakes which dwarfed the car's 16"-wheels; the unusual shaft-linked brakes were originally to have been part of a planned[citation needed] four-wheel-drive system which never came to fruition. The rear independent suspension used a low roll centre swing axle system, where a beam attached to each hub was mounted on the opposite side of the chassis. Thus, the beams were aligned slightly differently and crossed over in the centre line. Cornering forces did not jack the car up, as occurs with short swing axles. The car's fuel itself was also odd - a high-octane fuel mixture of 65 percent low-lead gasoline and 35 percent benzene; in some races, alcohol was also used to further increase performance. As a rule, the car left the starting line with 44 gallons of fuel and more than nine gallons of oil on board, although Moss and Jenkinson began their assault on the 1955 Mille Miglia with as much as 70 gallons of fuel in the tank[1]. At Le Mans in 1955, the 300 SLRs were also equipped with "air brakes" similar in principle to those used on aircraft - this was a large hood that hinged up behind the occupants in order to slow down the cars at the end of the fast straights. The idea for this "wind brake" came from director of motorsports Alfred Neubauer, who was looking to develop a system to reduce the wear on the huge drum brakes and tires during long-distance races such as Le Mans and Reims. Neubauer foresaw wind resistance slow the car especially at Le Mans, as the French track's layout forced drivers to use the brakes hard and often to bring the car down from its maximum speed - around 180mph - to as little as 25mph[2]. In tests the 7.5ft² light-alloy spoiler slowed the car dramatically and improved cornering. In addition, this innovation was required as the car's traditional drum brakes were inferior to the new disc brakes of main rival Jaguar. The SLR also had two seats, as required for sports racing cars of the day. In some racing events a co-driver, mechanic or navigator was given a ride. In the 300SLR's short career, this was only the Mille Miglia, as the 1955 Carrera Panamericana was cancelled due to the Le Mans accident. On short circuits (this includes the Targa Florio) passengers were not helpful, thus the passenger seat was covered and the passenger windshield removed to improve aerodynamics. Nine W196S chassis were built.

Of the nine W196s chassis built, one was destroyed in the Le Mans disaster. Of the eight that remained (and prior to the accident) Mercedes motorsport chief Rudolf Uhlenhaut had ordered two to be set aside for modification into a sort of hybrid between the SLR and the SL, featuring a slightly widened version of the SLR's chassis with enclosed bodywork for aerodynamic purposes. Again, the strong, high sill beams of the spaceframe required the fitment of the same famous 'gull-wing' top-hinged doors of the other two types. For testing, and in preparation for a possible Mercedes participation in the 1956 race season, two road-legal SLRs were built. After the disaster, and Mercedes' planned withdrawal from competitive motorsport at the end of 1955, the programme was abandoned, leaving Uhlenhaut to use one of the cars as a company car.

Stirling Moss drives his Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR to win the May 1955 Mille Miglia race.

Stirling Moss drives his Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR to win the May 1955 Mille Miglia race.

Posted 10/20/08 @ 12:02 PM | Tags: Mercedes SLS, 1955 Mercedes SL, American SLR, Chuck Porter, Sports Car Illustrated November 1956, Jim Mourning author, Russ Kelly author, Porter Special