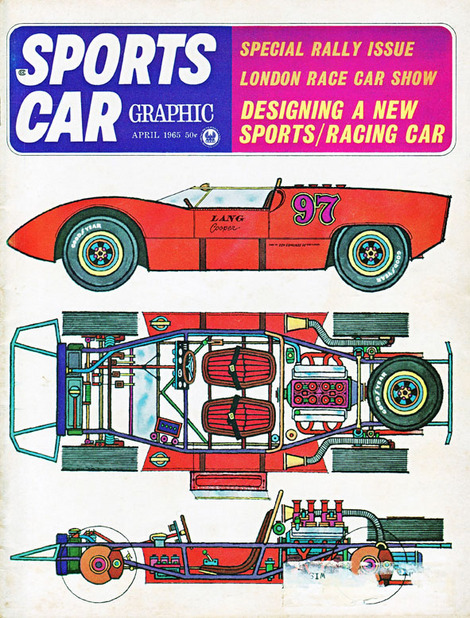

SHELBY AMERICAN'S PETE BROCK

SPORTS/RACING CAR DESIGN:

SHELBY AMERICAN'S PETE BROCK

by Jerry Titus photos: Dave Friedman and Darryl Nurenberg

THE AUTOMOTIVE STYLING DEPARTMENT OF LOS ANGELES' ART CENTER SCHOOL has been turning out polished students fro many years now. A large percentage of these go directly to Detroit studios upon graduation. Most of them soon digress to Product Design: things like toasters, drill motors, luggage or similar uninspiring subjects. The remainder find themselves occupied with small segments of the automobile; instrument panels, tail lights, grills, and so on. Once their talent is proven, they learn a new definition of the word Stylist, as they become as deeply involved in the total design of the vehicle as the Engineering Department does. Simultaneously, they discover the stark and restrictive realism of a Corporate World, a world governed by Cost, Practicality, and Politics. To a creative mind, it is a frustrating experience that leaves three choices - conform, be permanently shelved, or quit.

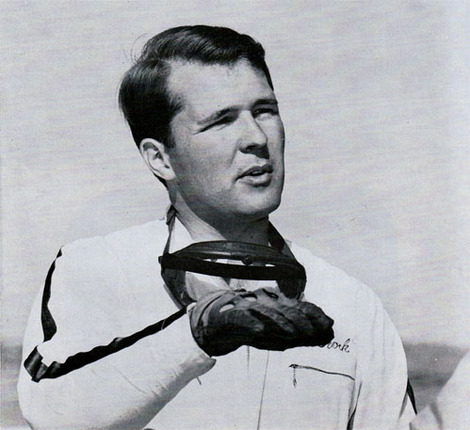

Driving-instructor/body designer Brock describes a cornering attitude to a student.

Driving-instructor/body designer Brock describes a cornering attitude to a student.

A former Art Center student, Peter Brock wound up i General Motors Styling. Demonstrating his talent, he was soon involved in a project that ultimately evolved as the Corvette Sting Ray. In his spare time, he developed a design for a unique economy sports car; a fastback coupe on a 67-inch wheelbase that would sell for approximately one thousand dollars. This was in 1958 - the Era of the Whale in Detroit. But market research was already indicating a need for such a vehicle and Brock's superiors took interest in his project, gave him assistance to develop it to a full-sized fiberglass prototype that lacked only a power-train. Pete's moment of truth arrived when the car was displayed for management approval. Harlow Curtis, then GM President and Board Chairman, took one look, announced he didn't like small cars, and walked away. It was the proverbial kiss of death and the project, coded Cadet, was soon gathering dust. It is a small consolation to Pete, after having his best efforts drop-kicked out the window so lightly, that the concept was later revised to the XP-79, which ultimately evolved as the Corvair.

It wasn't too long before a disenchanted Brock decided to load his 1100-cc bob-tailed Cooper on a trailer and head back to the West Coast. Schooled in San Francisco, he had become fully indoctrinated into the sports car field via admiration for one Nadeau Bourgealt, a local and very talented specials-builder. But Pete felt things were currently more active in Southern California, so he settled in Los Angeles. After several successful races in his well prepared Cooper, he traded it for a Lotus 11. On his first outing with the new car, Pete tried to modify the Turn Six guard rail at Riverside and wound up with a basket case. Shaken, but not discouraged, the likable young fellow's sincerity and enthusiasm. Further, he was able to express what he had painstakingly analyzed about driving. Soon Pete was helping Carroll with his students and today is the schools chief instructor. As the Cobra emerged as more than a gleam in Carroll's eye, Brock became Shelby-American's first employee......doing just about everything BUT design work, with the exception of an occasional brochure, ad poster, or insignia.

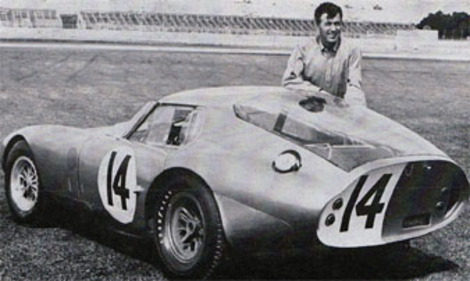

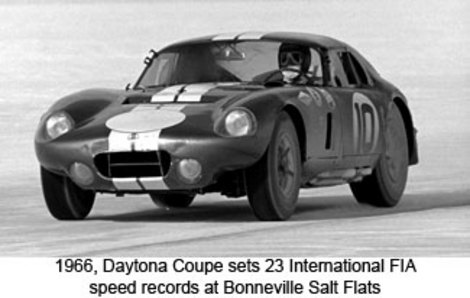

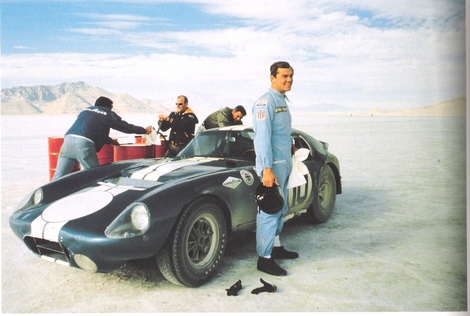

The Daytona coupe was his first drawing-board-to-track effort and as the grin of Shelby's face reveals, it proved a real success in racing.

The Daytona coupe was his first drawing-board-to-track effort and as the grin of Shelby's face reveals, it proved a real success in racing.

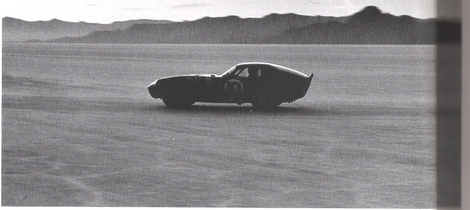

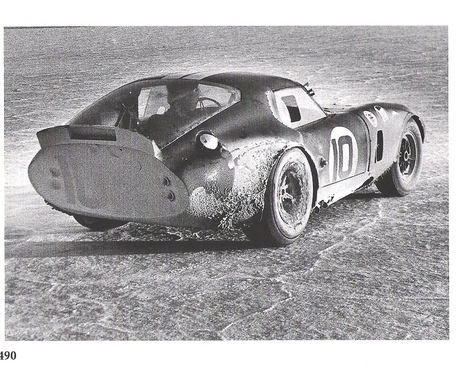

The Daytona coupe on track.

The Daytona coupe on track.

After swamping its opposition on U.S. Tracks, Shelby-American moved to take on the world's best. The need for an aerodynamic coupe became obvious if they were to be successful on such high speed circuts as Daytona, Sebring, LeMans, and Rheims. Pete sharpened his pencil and at last returned to the drawing board. The first outing of the season, Daytona, was only weeks away. His design package was limited by the existing chassis, engine location, seating height, and that now familiar bugaboo; Time. With only a practical background in aerodynamics based on observation and experimentation, he had buck some theoretical opinions against his design. At one point, Carroll asked a well-known aircraft aerodynamicist to examine the drawings. "It won't work," he opined. Here Brock's strong loyalty to Shelby got another boost. "Carroll looked a little sick," he remembers, "but he never asked me to change a thing, just patted me on the back ans sais he sure hoped it worked." It did. The quickly rolled-out body was mounted on a beef-up chassis and after a few frantic sorting-out laps at Riverside, was taken directly to Daytona, where its stability proved perfect.

A full lap ahead of its opposition at Daytona, Brock's coupe met disaster when it caught fire during a refueling stop and had to be retired. Refurbished, it went on to win the GT category at Sebring. It was at LeMans that the real test of aerodynamics came. With straightaway speeds exceeding the 180-mph barrier, the Ford GT and even Ferrari were having their share of problems. After the addition of a small spoiler on the tail, the Cobra coupe was completely stable above this velocity. Proof of it came after Schissler crashed the Ford GT in trials, climbed into the Cobra only a couple of hours later and set a new lap record. He did this while bandaged and wired up, still very uncomfortable from the accident, indicating the security of the Cobra at high speed.

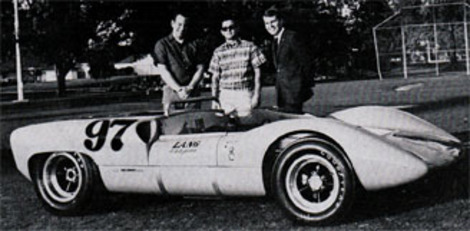

Body-builder Don Edmonds, owner Craig Lang and Brock pose with justifiable pride next to the beautiful Lang Cooper/Cobra.

Body-builder Don Edmonds, owner Craig Lang and Brock pose with justifiable pride next to the beautiful Lang Cooper/Cobra.

In action with Ed Leslie at the wheel.*

In action with Ed Leslie at the wheel.*

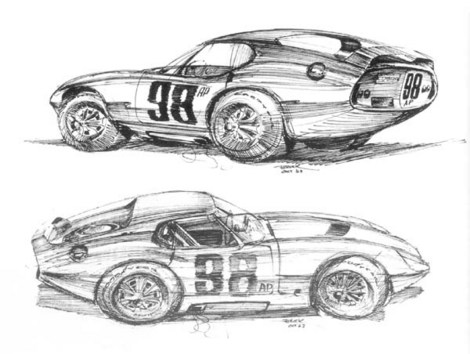

His Ability proven, Brock was given the responsibility of future Cobra designs, along with some outside projects like the proposed DeTomaso. "I got a note from Carroll telling me to have the drawings ready in one week and deliver them to Italy myself." Pete arrived to find the dimensions changed quite a bit from the specifications he was sent and was forced to redesign on the spot. THe original configuration wound up as a body for the Craig Lang Cooper. This handsome machine was admired by everyone who saw it last Fall when it appeared in the series of pro races. Duplicates of the shell were made for the Shelby team ex-Cooper "King Cobras," but this has been temporarily shelved during the development of the Ford GT, GT 350 Mustang, and the 427 Cobra. Latest of Pete's efforts include an updated coupe design for the 427. He told us simply that this one would have less drag and improved internal ducting, but Ken Miles later commented that projected mathematics on the configuration indicated a top speed in the 240-mph neighborhood! Squat and fat, the coupe's lines exude effciency as their prime purpose. Pete himself describes the appearance as "brutal", but we feel he's managed to include enough esthetics to make it handsome.

Married with a 17-month-old son, Brock is only 28 years of age and can look forward to a bright future of doing exactly what he likes best. His staff in now four-man unit and they're looking for motr outside projects, currently dickering for a design contract on a Japanese sedan, with a couple of other interesting irons in the fire. One of these is the nearing-completion Nethercutt monocoque sports/racing car, Pete having accomplished the primary design. He is busy in his "spare" time acting as technical advisor and doing stunt film driving for film work. We predict it won't be long before you hear a LOT more about the talented Mr. Brock.

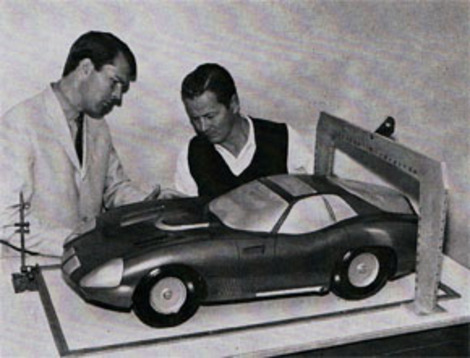

The shell will be duplicated on team cars. Pete outlines details of the coupe body he's designed for the 427 Cobra to SCG's editor, Jerry Titus

The shell will be duplicated on team cars. Pete outlines details of the coupe body he's designed for the 427 Cobra to SCG's editor, Jerry Titus

American Challenge Shelby Ford Shelby Film 1965.

History Daytona Coupe.

Other images and historical information:

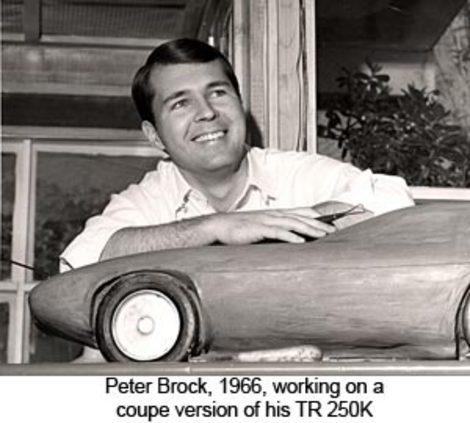

Peter Brock’s former career as an automotive designer with General Motors was never too far from his first love of racing. When he departed GM in ’60 he was deeply disappointed that the AMA’s ban on racing had killed all incentive for competition within GM. Now of legal age to race with the SCCA, he packed up his Cooper Climax race car and headed west to California intent on making it as a professional racer. In Hollywood he hooked up with Max Balchowsky of Ol’ Yellar fame. During the day he worked for Max at Hollywood Motors chasing parts, sweeping the shop and learning the arcane secrets of speed from one of California’s best tuners. At night he used the shop’s resources to work on his own race car.  Hollywood Motors was race central for many of the southland’s top racers in the late ‘50s. One of those who visited often was the gregarious Texan, Carroll Shelby, who was winding down an illustrious driving career due to a bad heart. Shelby was looking for a race related business to start and knew Max was a talent. Like so many others in that era Shelby had dreams of building his own sports car. Max didn’t need or even want a partner though, so that potential joint venture never jelled. Ultimately Shelby decided he’d start a driving school. Through a fortuitous set of circumstances, Brock was literally standing nearby when Shelby needed to choose who he was going to hire to instruct at his driving school. He thus became Shelby’s first paid employee. Brock is careful to explain that Shelby’s first real employee was Shelby’s girlfriend at the time; “She was the real brains behind Shelby American. It never would have made it off the ground without herâ€.  Brock, with racer friend and mentor Ken Miles, developed a curriculum that soon became known as the Carroll Shelby School of High Performance Driving. Brock had hoped his position with the school would lead to a seat on Shelby’s race team when the Cobra’s production line began but that program grew so quickly that Shelby soon had every top driver in the world standing in line to drive. Brock continued to instruct at the school and when it became successful enough he hired an assistant named Bob Bondurant. Shelby lost interest in the school when his commitments to Ford became priority number one so when he closed the school, Bondurant asked Shelby if he could take it over. Bondurant went on to make the school the great success it is today.Â

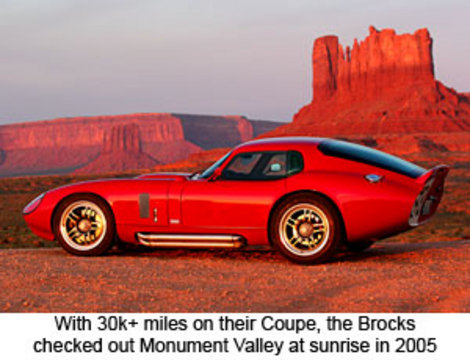

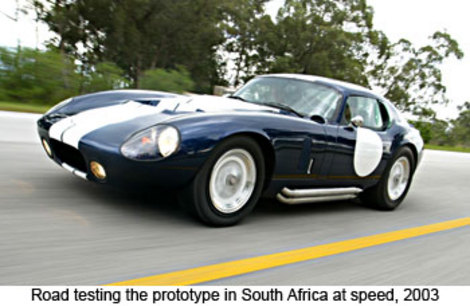

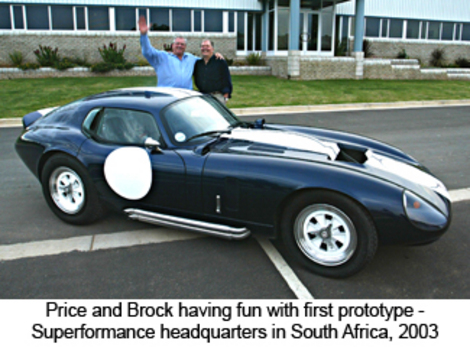

Design with Superformance

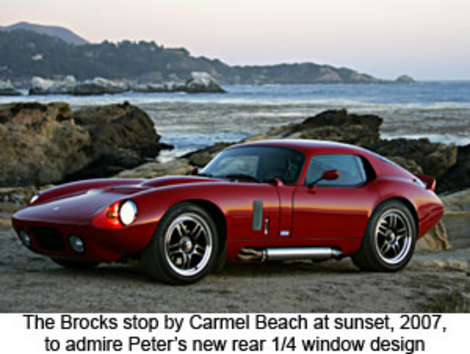

In 1999, Jimmy Price of High-Tech Automotive in South Africa invited Peter Brock to create a contemporary version of the Cobra Daytona Coupe he originally designed in 1964. This contemporary redesign of the World Champion Coupe for Superformance was never hampered with the design constraints of the original Daytona Coupe. The FIA rules for GT in ’64 had specified that the body or the chassis could be modified, but not both. The archaic 289 Cobra chassis was developed about as far as it could be by that time and the idea was to replace the blunt Cobra body with a more aerodynamic one. To conform to the rules, the Daytona’s body had to fit the existing 289 chassis. Only six Daytona coupes were built and they were designed specifically for racing. These design criteria called for minimum interior space (frontal area) and minimum creature comforts (weight).

Without these constraints, the Superformance Coupe could be designed as a real street-legal high performance GT coupe equally at home on the road or on the track.  Peter called in his old friend Bob Negstad from Roush engineering to pen the new chassis. Negstad had done the GT 40’s suspension while at Ford and now had all the latest state-of-the-art equipment at Roush’s to refine his ideas. The rear suspension features very long lower A-arms that pivot almost at the chassis centerline. This unique geometry allows the rear tires to remain in correct alignment with the ground over a wider range of suspension travel and cornering angles than any conventional suspension. The tires therefore stick better than those knocked off kilter by a less-than-optimum suspension geometry.

The Coupe’s new body shape was designed to conform to Peter’s original design philosophy for the 1964 Daytona Coupe which was based on some previously undiscovered aero-technology developed in Germany he had unearthed while working at GM styling in the late 1950s. Many subtle changes, such as an increased plan view radius for the windscreen and flush curved glass side windows were incorporated to improve the new Coupe’s aerodynamics. The resulting design is pure genius. To the naked eye, the new car looks to be the same size as the original Daytona Coupe, but is in fact slightly larger in every dimension, allowing for improved handling through improved chassis design and larger wheels and tires. The performance is also substantially improved with larger displacement versions of Ford’s venerable small block. There’s more interior space for increased driver and passenger comfort and the Brocks can tell you firsthand there’s an amazing amount of room for luggage. They currently have over 30,000 miles on their car, driving it on assignment to races around the country that they cover as photojournalists with all of their camera gear, track equipment AND street clothes.

Test of the Superformance Coupe.

The Cobra roadsters dominated the American tracks in 1963. Looking at the coming 1964 racing season, Shelby had his eye on European racing and realized he needed a new weapon to "whip Ferrari’s ass." Ferrari was the ongoing World Manufacturer’s champion year after year. The closed coupe Ferrari GTO's proved to be tough competition on the tracks of Europe. The Coupe had the top end needed on those courses. The Cobra roadster just wasn't fast enough to beat the Ferrari team. The open cockpit roadsters had the aerodynamics of a barn door. There was no denying the smooth, closed, body of the Ferrari GTO's gave the GT 250’s a tremendous advantage. Even though the engines in the 250’s were 2 liters smaller, they were faster on the long straight aways then the more powerful Cobras.

In 1962, Enzo Ferrari all but forced the FIA to accept the highly modified 250 GT Berlinetta as a "production coupe." The FIA rules stated that 100 identical cars had to be built in order for it to qualify to be raced. Ferrari had sold a lot more than 100 of the 250 GTO's. But a loophole in the rules existed for the small European manufacturers. They could make slight body modifications to allow for changes in technological advancements during the model year. The FIA called it "normal evolution of type." When Ferrari submitted the "modified" Berlinetta GTO that he wanted to race, it had more than a few upgrades. In the 1962 papers he turned into FIA, the racing Berlinetta GTO was given a new suspension, brakes, shocks, a magnesium-cased transmission and a new six-dual-throat Weber carb manifold on top of a 3.0 liter V-12. Ferrari did not submit the required photos of the "optional body." The FIA bucked and said the GTO was a new car and wouldn't qualify. Ferrari put a lot of pressure on them to accept it as a GTO. The FIA finally agreed. In doing so, Ferrari opened up the rules to special cars from other manufacturers like a lightweight E-Type Jaguar, the Aston Martin 212 coupes and eventually the Cobra Daytona Coupe.Â

The European racing cars were all built with engines at or under the 3.0 liter, the FIA limit. It was a lot more economical to use the existing tooling and molds in use for the production cars. The Ferrari GTO circumvented this requirement, too, opening the way for a 5.0 liter Cobra. The Ferraris were unbeatable. The GTO was the perfect car for this racing series at this time. No other manufacturer's car could keep up with them. During 1963, while the Cobras were dominating the American USRRC racing, Ferrari owned the European FIA circuit. The Shelby American Cobras did so well in the US that Ford agreed to back a Shelby effort against the Ferraris.

The power of the Cobras on the short American tracks was unbeatable, another right car at the right time in the right place. But on the longer European courses, speed was the key. The Cobras had run against the GTO's early in 1963. The open roadster, small block Cobras couldn't go exceed 160 mph. The closed coupe GTO's were considerably faster.

The aerodynamics of race cars was just being discussed seriously in the early 60's. Most people, thought aerodynamics belonged in conversations about jets. Wind tunnels and cars were never in the same conversation. A 24-year-old Shelby American employee named Pete Brock convinced Shelby he could develop a new weapon for the Shelby arsenal, a coupe. Brock was originally hired to run the High Performance Driving School at Shelby American. He was a graduate of the Art Center School in Los Angeles and the youngest designer ever hired by General Motors. At GM he did a lot of styling work on the Corvette Stingray during 1957-58. Brock was also Director of Special Projects at Shelby American. He was convinced if a closed coupe could be built, it would have the speed needed. Aerodynamics were the key, Brock was convinced. He said "he was influenced by some obscure German papers written by Wunibald Kamm." Kamm wrote about air flow and how important it was not to fight the air. Brock told Shelby it would take four times the horsepower to get a roadster to go 200 mph than it would to 100 mph. It would be a lot easier to reduce the drag of the cars than to increase the horsepower that much. And the car would qualify for FIA rules under the new interpretation used by Ferrari. The coupe project started in October 1963

Designing a Cobra coupe was not high on the list at Shelby American. Chief engineer at Shelby American, Phil Remington, didn’t think a closed coupe was the answer and basically didn't support the project. Brock drew up some designs working with Cobra driver, Ken Miles, and one of the fabricators, John Ohlsen. Miles believed in the project. So did Ohlsen, a New Zealander, who has just joined the team. But more importantly, Carroll Shelby was also convinced. The team was given Cobra CSX 2014 to form a body on. A plywood body buck was built on the 289 chassis. Aluminum panels were formed on the buck into a likeness of the coupe model. It passed the test. If nothing else, it sure looked like it could outrun the Ferrari’s. Not everyone was impressed the same, though. Benny Howard, an airplane builder from the 1930's, who stopped at Shelby American one day told Shelby it would take 500 horse power to move that body at 180+mph. The body design shape "won't work," Howard told Brock. Could the hot 289, so successful in the roadsters, provide enough horsepower to push the coupe to 200 mph?

Blueprints were sent to California Metal Shaping in Los Angeles for the body and inner panels. The first coupe was assembled at Shelby American as CSX 2287. The car did not look like any other car. The roof was odd shaped, the rear end was chopped off and it had a movable wing on the rear. These features didn't just look right to the rest of the Shelby team. But the die was cast and the coupe was assembled. Shelby backed most of Brock's design but he listened Phil Remington about the "ring airfoil" and opposed Brock on it. A compromise was reached. The car would be tested without the wing. If it was needed it would be added later. According to Pete Brock, the key to the success of the Shelby cars was the people picked to build them. The best fabricators and builders in Southern California came to Shelby American to see what was going on and what that Texan was up to. A lot of the new recruits were USAC racers, experienced in oval track racing. They may not have been engineers but they did have a lot of practical experience and Shelby trusted individual ability. They knew how to build cars that "went fast and stayed together", according to Brock. The Cobra Coupe was the final product of a group of experienced racers. Very few drawings were made and no formal engineers worked on the project.

At Riverside during the track tests, Ken Miles topped the track record by 3.5 seconds and also broke the Cobra record. Miles hit 183 mph without even pushing the car. It was 20 mph faster than the roadsters and Riverside's straight aways were not long enough to open it all the way. Brock had been right. Shelby was impressed and pleased. Miles however, felt the suspension wasn't stiff enough. One of the fabricators, Donn Allen had just joined the Coupe team. With his help, Brock's team put a triangulated subframe over the twin-parallel-tube frame to increase the torsinal stiffness. A basic roll bar added the finishing touches to the chassis strengthening. Over the weeks of testing, larger Goodyear racing tires were added making the car even faster. The tighter frame helped the bigger tires work even better to hold the Coupe to the track. And the car didn't demonstrate any lift at high speed. Brock still argued the coupe needed a rear wing for the European tracks but Shelby, Miles and Remington said the car was good enough and needed no more improvements. The only other changes made in preparation for Daytona was some small plastic fences attached to the windscreen pillars to divert the air coming off the windshield to the rear brakes for cooling and a couple of panels riveted on to cover the rear tires. By the time the car was ready for Daytona the team at Shelby American had a lot different opinion of the Coupe. Everyone was now excited about its debut on the Daytona track. It was being called the "Daytona car."

The first car, CSX2287, was tested at Daytona Beach in preparation for the Daytona Continental in February, 1964. Even though Deke Holgate, public relations manager at Shelby American, called it a Cobra Daytona Coupe named after its introduction at this race, the Cobra was rarely used to describe the coupes. They were just Daytona Coupes.Â

At Daytona, Shelby substituted Bob Holbert for Ken Miles as Dave McDonald's co-driver. Shelby considered Miles too valuable to risk on the track in an unproven car. Miles was real disappointed because the coupe was built around him. And he knew he could drive the Coupe to victory at Daytona. He tried to convince Shelby that he knew the car better than anyone else and he knew how to get the most out of it. But Shelby prevailed and made Miles team manager instead of a team driver. Shelby figured that with the experience of Holbert and McDonald in the roadsters, they would quickly learn how to drive the Coupe. After all the Coupe was a lot easier to handle on the track than the Cobra Roadsters. Both were right.

During the practice runs at Daytona, Miles set an rpm limit of 6,300. Holbert broke the GT lap record. The Cobra Coupes were three seconds faster then the Ferrari GTO's. Miles lowered the rev limit to 6,000 and Holbert still out ran the GTO's.

During the race, the Coupes were superb. By the end of the first couple of hours, the Couple lead the race by several laps. After six hours, Holbert came in to the pits complaining of smoke in the cockpit. When the rear tires were pulled off for replacement, it was obvious fluid was leaking out of the differential. The correct fluid wasn't available so Shelby told the crew to fill it with 50 weight engine oil till they could find some differential grease. Holbert hit the tracks again. Miles called him back in after a few laps to replace the engine oil in the differential. Since Holbert was in the pits, the fuel tank was topped off. The tank was still full from the prior pitstop. Gasoline spilled out of the tank onto the hot rear disc brakes and exploded. The car was immediately engulfed in flames. The wiring burned and the differential was finished. Shelby pulled the Coupe from the race. It turned out the cause of the problem in the first place was the seals deteriorated after the differential overheated. The inexperienced drivers in the coupe failed to turn on an electric circulating (a fuel) pump for the differential sometime in practice or early in the race causing it to get too hot. Miles knew about the pump and when to turn it on, the new drivers didn't. Could Miles have won with the Coupe? Would the differential have failed anyway?

After it competed at Daytona, the Coupe was reconditioned for the 12 Hours of Sebring coming in March, three weeks later. McDonald and Holbert made no mistakes this time and the won decisively. But the drivers baked in the car in the Florida heat. The Coupe hadn't been run for 12 hours before. The cockpit wasn't vented properly. Too much heat stayed in the cockpit. The team made some quick adjustments when they realized the drivers were suffering. Even though the modifications weren't enough, it helped the drivers survive the heat enough to win.

Ford was impressed with the performance of the Coupe and gave Shelby financial backing for a full assault on the European circuit. Five more coupes were needed. Four chassis’s were built at AC Cars in England then shipped to Shelby American for modifications. Shelby American was so swamped with work, the assembly of the coupes was subbed out. From the California factory, two out of the five chassis’s were shipped to Carrozzeeria Gransport in Modena, Italy. The plan was to also ship the prototype with the unfinished chassis to Modena for use as a model. But the prototype ended up in Sarthe, France, for official testing. Ford also sent two new GT40's. The GT40's were the center of attention for the press, Ford billed the GT40's as "the world's most technologically advanced race car." Both cars crashed during testing. The GT40's just weren't stable at speed. One of the GT40 drivers, Jo Schlesser, a French driver, who had crashed one of the GT40's, was given the chance to drive the Cobra Coupe. He loved the car. It handled so much better then the GT40's he was able to drive it to the fastest speed of the testing, 198 mph. Shelby asked him to drive the Coupe in some of the upcoming European races which he eagerly agreed to.

During the Coupe's first race at Spa, Brock's forecast of high speed instability was correct. Phil Hill found the car so unstable at over 180+, he brought the car in. The GTO's were more stable at high speed because of their tail wing. Phil Remington fabricated a wing for the Coupe the night before qualifications. The next day the Coupe handled so much better that Hill broke the track record and won the pole position. During the race, the Coupe lead from the start and held the lead until it began to have fuel problems. Hill pitted the car. Some kind of strange fibrous material was found in the tank. The filters and fuel pump were clogged. It took long enough to clear out the fuel system that Hill had no hope of catching up. Back on the track Hill gave one of the great heroic efforts in racing history. He not only caught up to the cars in laps, but broke the lap speed record three times. The fuel system clogged again and he was forced to pull in. The stuff in the fuel tank suggested sabotage but it could never be proven.

Meanwhile, Carrozzeria Gransport was trying to build the two new Coupes. Without the prototype to copy the design from, Gransport used their own disgression. The roof line didn't look right so they corrected the mistake giving the roofline a different contour. The error was discovered when the prototype finally made it to Modena. It was too late to correct the second Coupe, CSX2300. The two Coupes were shipped only days before the LeMans race to be prepped. The new Coupe, Chassis CSX2299, was assigned to Dan Gurney and Bob Bondurant. The prototype was given to Chris Amon and Jochen Neerspasch. The original prototype was definitely faster than the new coupe. In practice it was 11 mph faster in the Mulsanne straight away. The cars were identical except for the roofline. But during the race, Gurney driving the new coupe actually took his class and ran the fastest GT lap at 3:58.7. The prototype team was disqualified for an illegal start after the Ferrari team protested. It wouldn't start so the Coupe was jump started in the pits with a separate battery, definitely an illegal move. It was leading the GT class when it was black flagged in the 10th hour of the race. Ironically, the first "wrong roofline" Coupe was also the winningist Coupe. Dan Gurney was larger and taller than Ken Miles, who the coupe's seating was designed around. He fit better in the taller CSX2299. As the premier driver in many of the races, his coupes were better prepped and serviced, so he won more of the races despite the taller profile of the car. Gurney was also a very aggressive driver and won more races because of it. (The cars were not built with sequential numbers. CSX2287 was built and modified then used as a model for CSX2286 that became the pattern for CSX2299 and CSX2300. )

The Ferrari/Daytona Coupe battle continued the rest of season. The last race was scheduled for Monza, Italy. Ferrari lead by a few points. Shelby had four Coupes ready. Ferrari was in trouble. For the first time in years, it looked like Ferrari wasn't going to win the European Championship. Somehow Enzo used his clout to have the last race cancelled. Ferrari had more points than the Shelby team giving Team Ferrari the trophy once again. Enzo Ferrari couldn't win the 1964 trophy with his cars so he used what no one was expecting to win, political clout.Â

The next year, Ferrari pulled his team completely out of GT racing. He knew he couldn't beat that upstart Carroll Shelby's Daytona Coupes, so he didn't try. Instead, he went after Ford's GT40's in the Prototype Class. The struggling GT40 team just couldn't pull it together. Ferrari successfully won the Prototype class. Shelby's Coupes won the 1965 World GT Championship hands down. The Coupes won almost every race they were in. In fact in some of the races, they came close to out running the Ferrari prototypes and the GT 40's. (Ford threw in the towel on the GT40's after the embarrassing 1965 efforts and turned to project over the Shelby American with instructions to win with the GT40's and not the Daytona Coupes. The project ended there and the Coupes became a part of history.

Posted 01/10/09 @ 07:45 PM | Tags: Pete Brock, Sports Car Graphic April 1965, Daytona Coupe, General Motors Styling Department, General Motors, Harlow Curtis, Nadeau Bourgeault, Lotus 11, bob-tailed cooper, King Cobras, Ken Miles, Jimmy Price, Superformance Coupe, Ford GT 40, Hollywood Motors, Bob Bondurant, Sports Car Graphic magazine