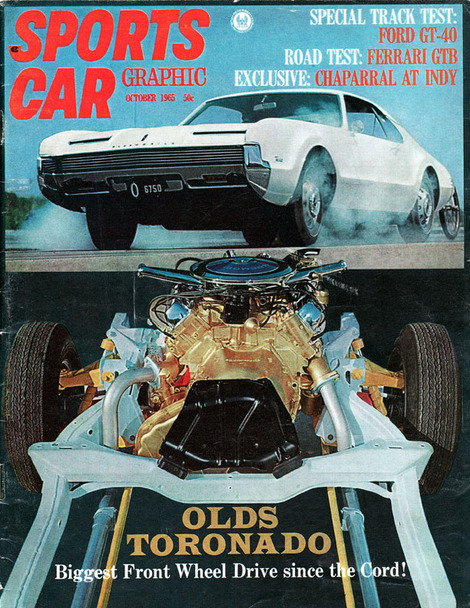

Chaparral at Indy

WIll Jim Hall build an automatic-transmissioned Indy Chaparral for next year's "500?" Wouldn't that shake up the troops.

Text & Photos: George Moore

NINETEEN-SIXTY-FIVE MUST GO DOWN IN THE BOOKS AS A BAD YEAR FOR THE OLD GUARD AT INDY. Not only did the rear-engined road race-bred equipment knock the wheels off the hallowed 500 roadster, but now low blow of all low blows, the era of the automatic transmission is rapping none too gently at the Speedway's front gate. The individual doing the pounding is Jim Hall, the automatic whiz kid from Midland, Texas. And while Hall is making no definite commitment at this time, his recent visit to Indianapolis to test the Chaparral's automatic gearbox was construed by most people at the track as indication he is now eyeing the 500-Mile Race.

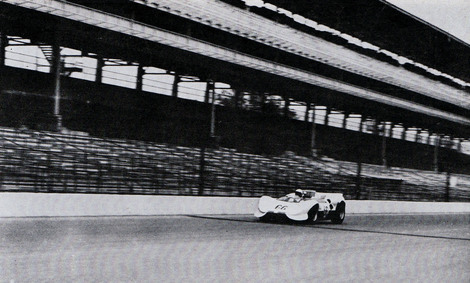

Boiling down the pit straight in front of the main grandstands, Hall holds the streamlined sports car in the fast groove of the 2.5 mile oval.

Boiling down the pit straight in front of the main grandstands, Hall holds the streamlined sports car in the fast groove of the 2.5 mile oval.

Hall was at the Speedway as a guest of Firestone, which was undertaking it's yearly summer test program. Between times, when the company's engineers were not on the oval, Jim was free to take a whirl at it with the Chaparral. Whirl it he did, working up to a lap speed of 145 mph. This was with but two day's practice, and with an automobile still set up in a road race form.

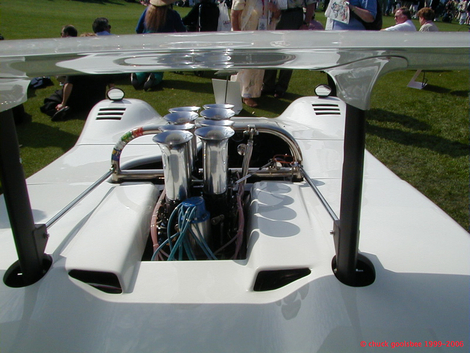

Some minor problems were encountered with the body at high speeds - the fenders tended to flap a bit - but this was remedied by bolstering the edges with aluminum sheet metal. Hall and his crew cut away the outside wheel well edges, then tacked on the sheet which flared outward to cover the outer shoulders odf the rear tires. The metal stopped the flex of the plastic fenders without otherwise disturbing the aerodynamics of the body.

Beyond that everything functioned as expected, with the Chevy putting forth its own special blatting sound, and the automatic transmission inconspicuously slipping the car out of the corners with short bursts of increased acceleration. Hall borrowed a page from Ford's notebook or perhaps it was the other way around, carrying an electronic recorder with him to tape engine rpms, shift points, etc., in the turns and on the chutes.

Jim was his usual affable, polite self, except he didn't tell anybody anything. He did admit he was thinking about Indy - especially since he was standing there with a USAC rule book and a 1965 entry blank in his hand - and he thought if such a car was built it probably would have an automatic transmission. Beyond that, everybody was sort of on their own.

Actually, the concept about which Hall is thinking is not new. The machines which have competed at Indy in the past could have utilized a moderate gear change, but so far nothing has been available which would be applicable to this type of racing. There is not a great speed differential between the straightaways and the corners. And the time element, plus the style of driving needed to get around the place quickly virtually negates any such thing as down shifting going into the corners.

The Chaparral exits from beneath the awning placed in the pits after a few minor body modifications were made to allow suspension adjustments.

The Chaparral exits from beneath the awning placed in the pits after a few minor body modifications were made to allow suspension adjustments.

The speedway is comprised of four straightaways and four corners. There are the two main long chutes, and two short ones which lie between No. 1 and No. 2 corners, and No. 3 and No. 4. The basic technique in establishing quick lap times with an Offy is to sort of "float" the machine into the turn without using the full decelerative force of the four cylinders, then get back into it at about the apex of the corner. With less deceleration from the Ford's V-8, a driver comes all the way off the power and flatfoots it quicker than with a Meyer-Drake.

There is approximately a 1200 rpm drop in engine speed, so what can be done with an automatic transmission is to obtain a very slight gear change or torque multiplication to either hold the engine speed at a constant rate or bring it back up to peak rpms in a shorter period of time. To be effective, it would have to be accomplished at the dictates of the engine. And if done properly, the car would jump across the short chutes as well as accelerate out of the corners onto the main straightaways more quickly.

Hall's Chaparral appeared to accelerate faster down the main chute than would be considered usual with this type of car. He followed the established groove in the corners, lying out next to the wall on the approach, dipping down to the inner white line about half way through the turn, and drifting back out as he powered his way onto the main stretch. However, turn speeds were rather moderate, so he had to be picking it up on the straights in order to turn a lap at 1:02.

Jim cuts away a section of the rear fender with snips to provide clearance once camber change was reduced to counter-act centrifugal loading.

Jim cuts away a section of the rear fender with snips to provide clearance once camber change was reduced to counter-act centrifugal loading.

Jim did state his transmission could be set for a road course so the power didn't break the wheels loose off the slow corners. With the wide tires now in vogue at Indy, nobody is spinning the wheels on the forward traction. As a consequence, the mechanics in the area felt that a minor differential rate of gear velocity in order to keep the V-8 working within a more limited rpm range was exactly what Hall was looking for.

The one-gear-only brand of thinking which has dominated American closed course racing has hampered U.S. race car transmission development seriously. But with the narrowing of the gap between road race cars and Speedway cars, it need not be fatal. It was this closer relationship between Formula 1 automobiles and the Indy equipment that got Hall interested in the 500. The association probably will result in some design changes which will be as profound as the switch from the front-engined Offy roadsters to the rear-engined Fords.

EDITOR'S NOTE: To see if there was a possible and further significance to Hall's Indy experiment, we checked with him just prior to press time. Jim's answer was a "No, not at this time" as far as any intent toward participation was concerned. He explained he was mainly curious to see what Indy was like and chose to do so in a machine completely familiar to him. "We would have liked to stay around and set things up to see how fast we could go, but it was before Watkins Glen and we didn't want to wear the car out."

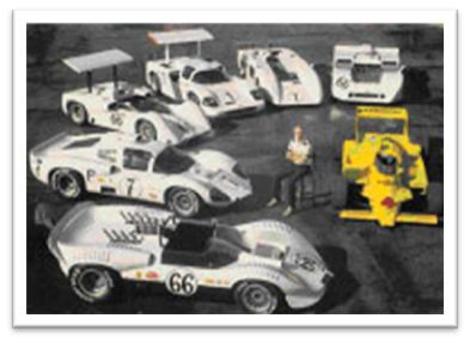

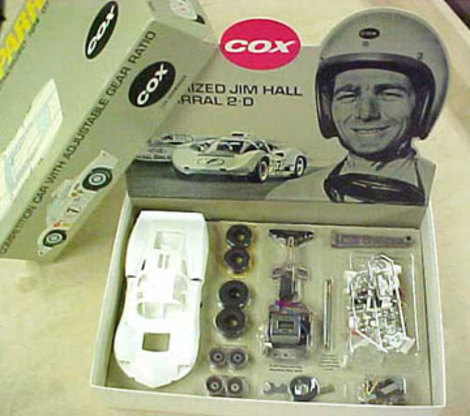

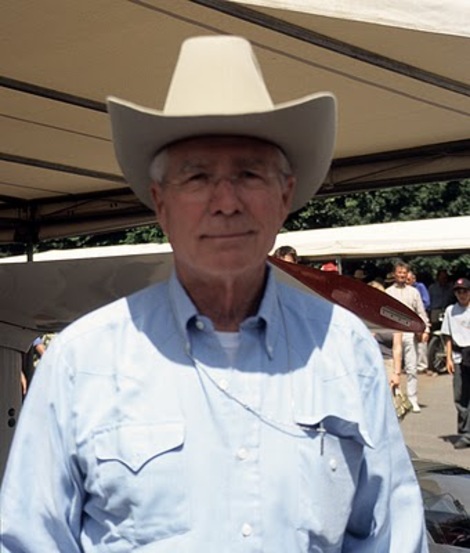

Jim Hall inspects Chaparral 2D

Some other photos of the incredible Chaparral and Jim Hall

Jim Hall is truly one of Americas greatest car designers and drivers of that period of history. Check out the other article posted here earlier - Jim Hall's New Chaparral 2-C

Posted 05/22/10 @ 05:19 PM | Tags: Indy Car Racing, Jim Hall, Chaparral, Sports Car Graphic magazine October 1965, Firestone, Ford, Offy, Meyer-Drake Offenhauser, Jim Hall at Indy, Indy 500