Double Test: 427 Cobras for Street & Competition

At a recent swap meet I found a gentleman selling old magazines. An hour later I dragged a huge bag of sports car and hot rod magazines from the 40’s; 50’s; and 60’s around with me for the rest of the day. But it was well worth it!

This is the first in a series of articles I plan on recreating on everything from sports cars to hot rods from articles that are out of print and I believe still of interest today.

Everyone LOVES Shelby Cobras! They are truly the American icon of production sports car racing.**

I own a Superformance Cobra myself.

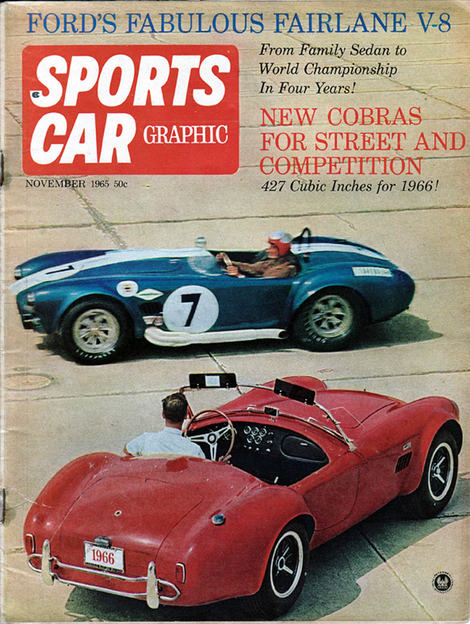

This is an article taken from Sports Car Graphic magazine November 1965.

A Cobra article was first published there in May of 1962 - The editor was quite taken with the Cobra.

It was written by John Christy then editor and Jerry Titus of Trans-Am fame.

John Christy went on to Motor Trend and Car and Driver in his career. He also was reputed to be a very good friend and drinking buddy of Carroll Shelby.

Shelby invited him to take a look at the new 427 Cobra.

Jerry Titus won the 1967 Trans-Am Championship and placed third the next three years. He is a sports car racing legend.

For those Cobra enthusiasts this is a must read article. It goes into quite a lot of technical information about the cars and performance. Do not cry when you see the price in 1965.

D O U B L E T E S T:

4 2 7

C O B R A S

FOR STREET & COMPETITION

By John Christy & Jerry Titus

(recreated from Sports Car Graphic: November 1965)

As a number of people have found out, when you have a world beater on your hands, be it automobile or outhouse, you don’t just sit back on your laurels and expect people to let you get away with it.

So it was, and is with Carroll Shelby and the Cobra. In 1964 and 1965, Shelby had the Production car world by the tail with his 289 Ford-powered “snake.†Except in very rare instances, where all-out effort was coupled with all-out driving ability, the Cobra was unbeatable. It did not look as though anybody who would, could beat it, and those who possibly could, wouldn’t.

Nobody could have blamed Shelby if he had sat back and rested on his and his crew’s achievements. But Carroll & Co, including such foxy types as Ken Miles, have been around a good while. As we said, 1964 was strictly The Year of the Snake, but since the day when we walked into a small stall shop and helped put the finishing touches on totally unpainted Cobra#1, we’ve made a point of keeping an eye on the ever-growing snake pit.

So it was that at Sebring in 1964, even though we had other fish to fry (somewhat inauspiciously) we made a special effort to b e around the Cobra quarters, having heard earlier that the ubiquitous Mr. Miles had shoehorned a monstrous Grand National type 427 cubic inch Ford into one the team cars. Sure enough, he had.

He also managed to mow down the only tree in 5 acres of open ground when the beast got away from him coming out of the Esses in early practice sessions, and was busily pounding out the divots in the car when we made the scene. We decided this was no time for idle conversation and went elsewhere to attend to our own machinery.

The light weight version of the powerful 427 used in the race cars has aluminum heads and other parts to make some 80 lbs. lighter.

The light weight version of the powerful 427 used in the race cars has aluminum heads and other parts to make some 80 lbs. lighter.

During practice we made it a habit to glance nervously in the mirror when coming onto a straight. If what we saw in the glass was blue with white stripes (or red), we moved over right now, due to the fact that whatever it was, was going to over take right now. On one occasion we looked in the mirror, and saw something blue with white stripes. We moved over and waited, and waited, We waited until we got about two thirds of the way down the straight. Suddenly there was this godawful explosive roar and our car picked itself up and set itself down at what felt like about three feet to the right. Something blue with white stripes was disappearing around the next turn. Ahrrgh!

The next question was: if he was going so bloody fast why did it take him so blasted long to get there? We found out the answer later. Every time Ken rounded a bend and headed down a straight the beast just sat and scratched until, eventually, it caught a bite. at which point everything was peachy keen until the next turn. So much for history: suffice it to say that the debuts of both cars, his and ours, were somewhat less than satisfactory. Tires available a the time and the buggy spring suspension of the older Cobra just weren’t up toi handling the 480-odd Percheron that lived under the hood. It also got more than somewhat warm in the cockpit.

The second appearance of this monster, widened, beefed, vented and with much bigger tires was Nassau ’64. It still had buggy springs but not much else was the same. It went like the hammers and was only beaten, and just by a lightweight GS Sting Ray in the hands of Roger Penske, and then only because some chassis bits broke up and Ken had to slow down.

We thought it had still to be only an exercise and something to keep the Shelby competition department busy in odd off moments. Surely Ol’ Shel wasn’t actually planning to build 100 of these brutes and turn them loose on the body politic? He for dadburned sure was! Fun is fun, but Shelby wasn’t spending loot sending the prototype around to odd parts of the world just for the kicks of seeing Miles stuff his hoof into more horsepower than most people use in a lifetime. If the car was going to qualify for SCCA production racing he had to abide by the rules and build street machines. One full hundred of them.

By this time Miles and Jim Benavides, the project engineer, had decided that this could not be just a mob job on the 289. It had to look like a Cobra 1, but that was about all. So they started with a relatively clean sheet of paper and built a new car.

First, Shelby’s comment that “It works†notwithstanding, that transverse leaf spring suspension had to go. Second, everything else had to be bigger and stronger to take the torque and heft of the giant 427-cubic inch power-plant, a unit that was designed to push 4,000 pounds of brick-like sedan at 170 mph. In fact everything had to go but one item - surprisingly enough the standard Salisbury rear-end used in the 289 was found to be more than sufficient.

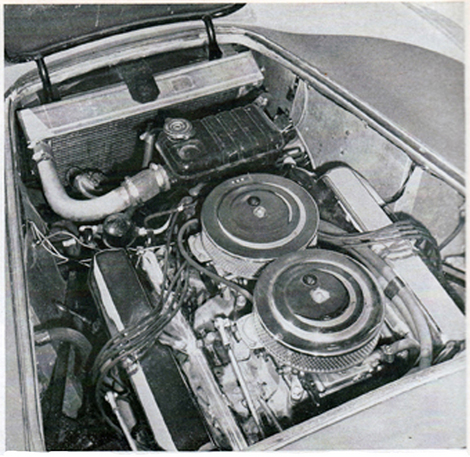

The street 427 has two Ford-made four barrels supplying fuel to the powerful engine - This set-up produces as much torque at the bottom end as the competition version.

The street 427 has two Ford-made four barrels supplying fuel to the powerful engine - This set-up produces as much torque at the bottom end as the competition version.

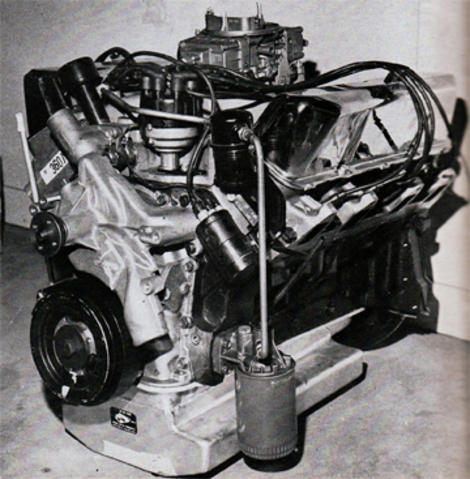

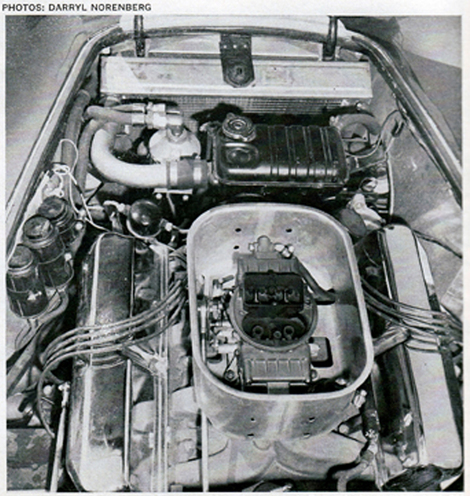

*The racing 427 uses a single Holley with its centerivot floats - it is rated at 780 cfm - Output from the 7000-cc monster is 485 horses with 480 ft. lbs. of torque.

*

*The racing 427 uses a single Holley with its centerivot floats - it is rated at 780 cfm - Output from the 7000-cc monster is 485 horses with 480 ft. lbs. of torque.

*

There can be few complaints about trunk space in the street version - It has lots of room

There can be few complaints about trunk space in the street version - It has lots of room

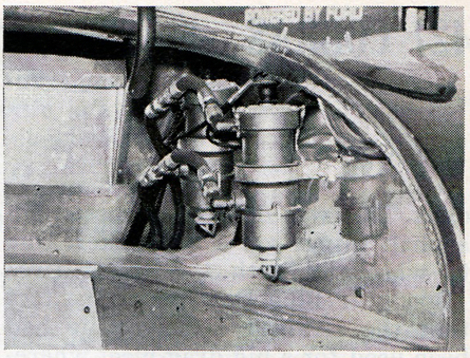

Hidden in the upper/right corner of the race car trunk is a pair of heavyduty fuel pumps.

Hidden in the upper/right corner of the race car trunk is a pair of heavyduty fuel pumps.

Intregral coil-shocks, as used on virtually all modern race cars, were selected both for compactness and ease of adjustmentfor chassis tuning. This naturally, necessitated a complete redesign of the front and rear structure to carry the necessary upper A-arms that replaced the leaf springs which formerly located the upper ends of the hub carriers.

The frame tubes went from three to four inches in diameter and were moved 22 inches apart, from the original 17 as on the 289. The body design is that of the 1965 competition version and drops straight to the frame instead of tucking under as before. To make room for the bigger bell-housing the pedal support box no longer straddles the frame, but is moved out with the widened tubes, thus offsetting the pedals to the left. This is disconcerting at first, but can be gotten used to in a day or so.

Bigger hubs carrying bigger, more widely spaced bearings, taper instead of roller, are used in the 427. Bigger,much stronger half-shafts are used and through these are splined, the rear suspension geometery is such that only 0,020 of an inch of spline movement occurs in spite of more than six inches of wheel travel allowed. Designing the axle for splinetravel would have been useless in any event, according to Miles, since the splines would bind up solidly under the brutal torque of the big-incher.

For the street machine, the suspension mountings are rubber, and an option of bronze bushings is setup for the race car, In the street machine the engine is an out-of-the-box, Grand National 427, fitted with two AFB Holley carburetors as used on the Mustang. These have fairly small primary ventures and big secondaries. Thus the street Cobra is fed gently at the outset and is, if anything more docile than the 289 if one remembers that the first throttle stop is only a detent to remind you that the big secondary vents are about to open. On the race car the feeding is done by one great huge Holley 780 cfm as used on NASCAR machinery, sitting in a bath-tub-like cold air box. Even this one is fairly docile at first, but it comes on much more rapidly. The carburetors on the dual set-up tend to flood or starve on very tight turns: the big single, with its concentric float, does not - most definitely not.

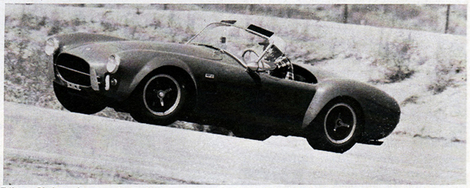

So it’s docile at first. However, if one is in either of the two lower gears one is advised to make sure the rear end has caught a bite before one goes beyond that first throttle detent. This Haug will lay great huge strips of rubber if treated disrespectfully at any speed in either first or second, and will even do it in third gear if it is the least bit out of shape. Treated with respect, the 427 is smooth and very deceptively fast in either top speed or acceleration.

Tests at Riverside.

Tests at Riverside.

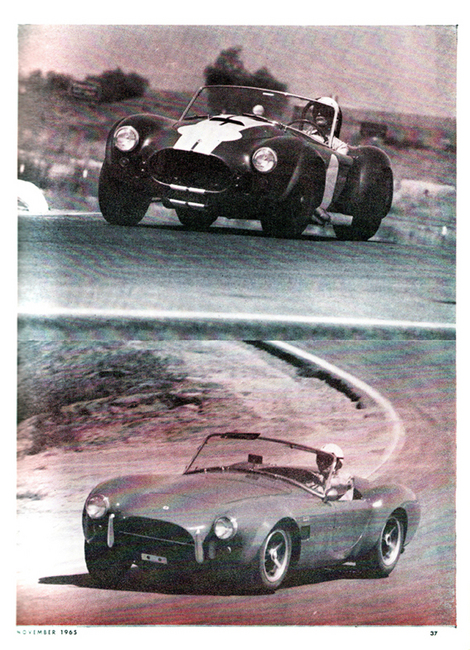

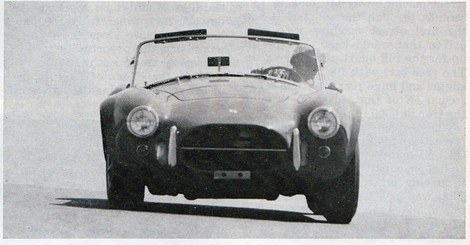

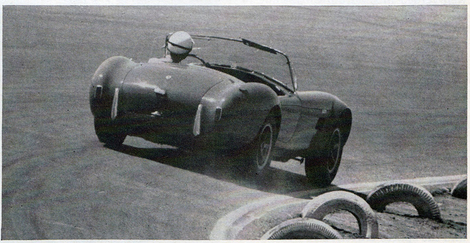

The street version with its smaller-section tires - develops some oversteer when accelerating through a corner, but its manners are exceptionally mild for such a hot performer.

The street version with its smaller-section tires - develops some oversteer when accelerating through a corner, but its manners are exceptionally mild for such a hot performer.

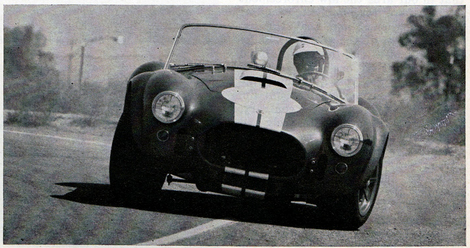

Titus caught in the act! With low tire pressure, the race car's understeer used more road than he figured on.

Titus caught in the act! With low tire pressure, the race car's understeer used more road than he figured on.

Once upon a time, Austin Martin made a big thing out of going from zero to 100 and back to zero in less than 30 seconds. Ken Miles took one of the street 427 machines out and did zero to 100 to zero in 13.2 seconds. This was done on concrete. On asphalt things get a bit slicker. Due to wheel-spin with the street tires (Goodyear Blue Dot), and the fact that the straight at Riverside had been used for a big drag meet wherein several cars had grunched on the line, the best we could get with the street machine was 100 mph in 13.2 seconds through the quarter. It was the first street machine we’d ever driven that would keep the tires lit up for the full quarter in every gear. The race car, with its “blueprinted†engine and huge rear tires, got a second off that, blasting through the trap at 6500 in third gear.

At one point we were entering a freeway and pausing at the entrance. Our passenger looked at the traffic and commented “Careful, the traffic is moving pretty fast - wasn’t it!†That was how long it took to get up to and above the normal 70 mph flow of cars. To be very blunt about it, we do not advise those not extremely well-versed in Cobra mystique to try the shenanigans conducted by Ken Miles in this car.

Looked at as a whole, the Cobra 427 is not a machine for general transportation. It is rather the latest example, and very probably the pinnacle, of that vanishing breed, the pure sports roadster. Its water-tight integrity is on the minimal side, and it wouldn’t be much fun to drive in most urban areas, particularly east of the Mississippi. It can be used for travel and there is considerably more room in both trunk and cockpit than in past versions, but best the weather be good and spaces travelled be wide.

Our best car of the street version was bright red and we were thankful that in our area the law enforcement agencies are reasonably tolerant of such machinery, and that the exhaust system of the 427 is virtually silent except at full throttle. Painted red, this car is one that in some areas could get you a ticket while parked in the driveway. To sum up, our early misgivings to the contrary, the Cobra 427 rides comfortably and is bags of fun as long as long as one puts the brain in gear before putting the car in gear. One might get a bit wall-eyed keeping one eye on the road and the other on the rear view mirror, but that’s been the name of the game for years, and a small price to pay for the privilege of driving a machine not seen on the road since Mercedes raced cars in the 1930’s.

Strong magnesium wheels of the pin-drive type, with knock-off hubs, are standard on the Cobra.

Strong magnesium wheels of the pin-drive type, with knock-off hubs, are standard on the Cobra.

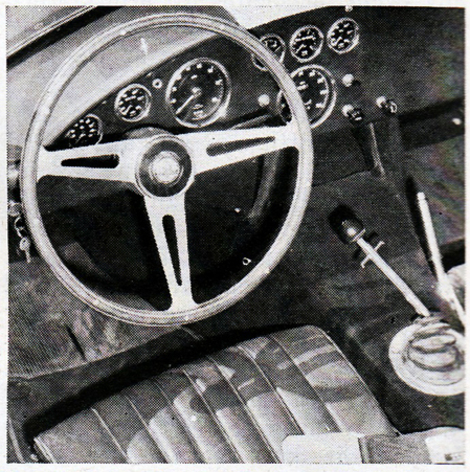

Fully-instrumented cockpit is simple and neat in the very best of performance-car tradition.

Fully-instrumented cockpit is simple and neat in the very best of performance-car tradition.

Editor Christy barrels the street version in an uphill turn on the fast Riverside circuit.

Editor Christy barrels the street version in an uphill turn on the fast Riverside circuit.

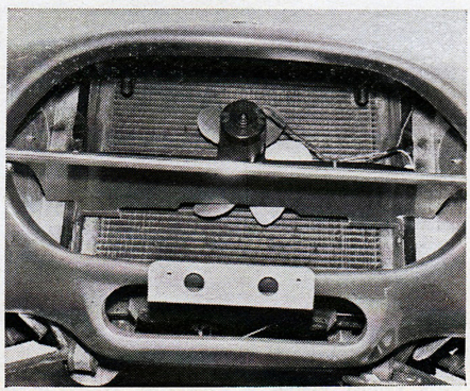

The street version is equipped with an electric fan for emergency use in hot-summer traffic.

The street version is equipped with an electric fan for emergency use in hot-summer traffic.

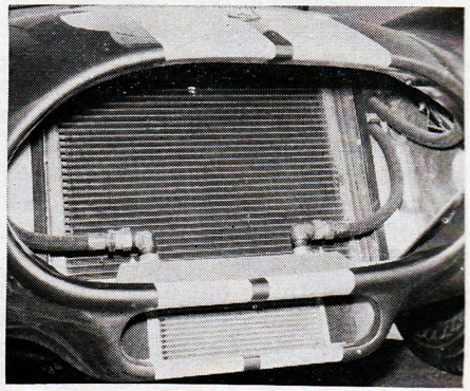

The racing version has its oil cooler mounted in a rather vulnerable position under the grille.

The racing version has its oil cooler mounted in a rather vulnerable position under the grille.

We tested both the street version and the track machine. For this last, we will now turn you over to Jerry Titus:

Last Spring: Ken Miles debuted the competition 427 Cobra in the Riverside USRRC. Naturally, he had to run it as a Modified at that time. Aboard the Webster Two-Liter, we sat in hids truck for quite a few laps and had a good opportunity to watch the suspension work. It wasn’t very impressive, but the thing stopped and accelerated like the best Modified on the track that day. A lot of careful development has taken place since track with a 427 - this time in the hands of Skip Scott - at the recent Continental Divide US-RRC (see Boss? We’re out there evaluating other equipment when we are racing). This time the results were impressive. Scott was getting goodly amounts of power to the ground coming out of a corner, and quite a bit more bite under all conditions than the original prototype did.

Power is something the 427 has plenty of, yet the race car version uses the single four-barrel Holley carburetor as opposed to the two quads on the street version. To reduce engine weight, cast aluminum heads, oilpan, high-riser manifold, and timing-chain cover are part of the competition package. This pares some 80 pounds from the stock 427. Torque is ample to bust the rear wheels loose from 2900 to 6500 rpm, so the gearbox ratios are fairly widespread by race car standards.

The shift handle is long but positive, with the throw very firm and very short. In the bottom three gears, delicate use of the throttle is required if you wish to continue heading in the direction desired - even with a machine that grosses (with fuel and driver aboard) in the neighborhood of 2700 pounds!

Obviously, the 427 Cobra is a brute. There’s no other word for it. So the majority of the effort in the race car version has been concentrated on helping the chassis cope with the performance. Huge Koni adjustable shocks are installed in both front and rear. Spring height is also adjustable via a screw-up collar that acts as a lower seat for the coils. CR Girling calipers up front and RR units in the rear clamp on 11-inch discs that are 9/16-inch thick. The stop-ability of the heavy machine is strictly amazing. These are real anchors and the suspension works well in combination with them for maximum stopping stability: there’s a lot more squat than nose-dive. Cooling air ducts of fiberglass are provided for both front and rear discs.

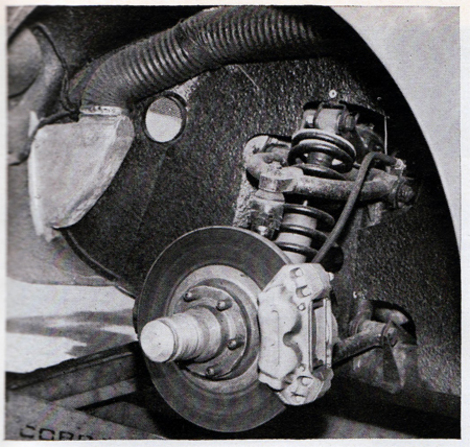

The street version has big 10.75 inch discs with unequal-arm suspension, coil/shocks, and front sway-bar. Duct brings fresh air into the cockpit. Notice the full undercoating.

The street version has big 10.75 inch discs with unequal-arm suspension, coil/shocks, and front sway-bar. Duct brings fresh air into the cockpit. Notice the full undercoating.

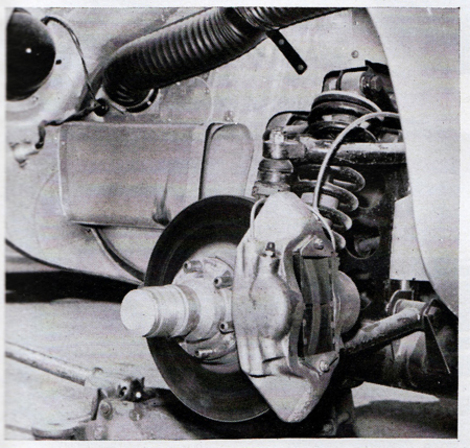

The race car is equipped with binders over 11.5 inches in diameter and heavy duty calipers to make it well able to handle the potential of the engine. Fiberglass duct brings in cool air.

The race car is equipped with binders over 11.5 inches in diameter and heavy duty calipers to make it well able to handle the potential of the engine. Fiberglass duct brings in cool air.

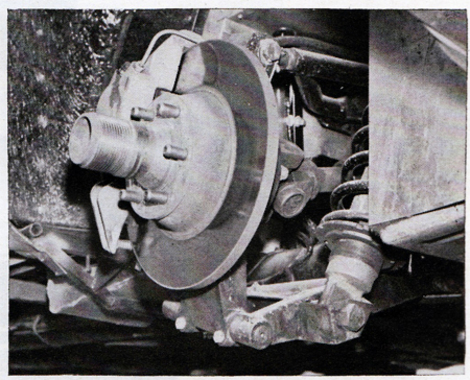

Fully independent rear suspension is now the feature of the Cobra, via the addition of the upper A-arm, Armstrong coil/shocks are adjustable to both car-height and dampening dampening setting required.

Fully independent rear suspension is now the feature of the Cobra, via the addition of the upper A-arm, Armstrong coil/shocks are adjustable to both car-height and dampening dampening setting required.

The cornering power of the competition car is excellent. Our test was provived with 15 x 8 Halibrand mag wheels up front and 15 x 9 rears. We understand that rim width and tire cross section are soon to be increased further. There was only one problem with our test car: the original bronze bushings were not installed at suspension pivot points and the normal rubber bushings allow considerable fore and aft movement of the suspension. Accelerating out of a corner, we found that the line would change two or three times as these rubbers loaded and unloaded. The word is that, selling for $9,500 per copy, the full race version actually represents a one-grand loss to the factory. Hence the attempt to recoup some of it by offering options like the bushings, a few more minor goodies, none of which were on the one we tested.

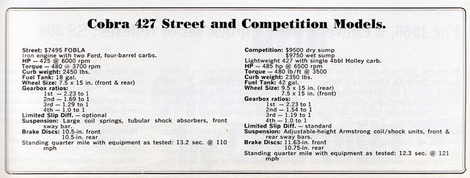

The specs - don't cry over the price back then - who knew?

The specs - don't cry over the price back then - who knew?

The cornering attitude of the car can be altered by suspension adjustment. As set, this one had strong understeer. It had terrible understeer until we discovered the front tires had only 26 pounds of air. These were pumped up to 36 pounds (thr rears left at 22 lbs.) and, by golly, it would turn a corner after all. We would have liked still less of it as, even with relatively light steering pressure, it took a lot of horsing and a very hot approach to get hung into drift that would allow the power to be turned back on. Otherwise, throttle-application only produces more of the “lets-go-straight attitude.

Straight-line performance is something out of this world. Playing around with a couple of quarter-mile runs, we hand-timed it at 12.3 seconds. Set up for dragging, it could probably better that considerably. Above 130 mph, the wind-buffeting lets you know it’s aerodynamically a big brick, but the only instability is when slight bumps produced wheel spin. Top speed is reportedly in the 180 mph category. The equal of any big production sports cars in a corner, it will get around even tight circuits in impressive lap times. Miles has logged laps in the 1:35 category while testing at Riverside; a very solid Production-car record and a little over six seconds below the absolute track record. We would have liked to have tried for lap times with the unoptioned version, but four places on the track were dug up to put in waterlines. (Yes sir, we said “water.†There’s even a square acre of green grass in the infield ). Even the unoptioned car has to be as quick as the best 289 Cobra and since both are classified by SCCA in A-Production, it will soon make the latter obsolete. Its pretty hard to argue with 480 horses, which is roughly what a tuned 427 puts out with complete reliability, and with torque like a dump truck.

Posted 09/11/08 @ 03:47 PM | Tags: 427 Cobras, 427 Street Cobra, 427 Competition Cobra, Carroll Shelby, John Christy, Jerry Titus, Sports Car Graphic magazine, road test 427 Cobras, shelby cobra